In the Shadow of Cerro Rico

Hope & Hardship In The Shadow Of The Rich Hill

Esperanza y dificultades a la sombra de la colina rica

Words and images by/Palabras e imágenes por: Benjamin Paul (ig)

Don Sîmon's right eye was discoloured and glassy as he sat stoically, chewing coca leaves, in a small shack outside his mine on the Cerro Rico mountain above the city of Potosî, in South-western Bolivia. The dynamite accident three weeks before had robbed him of the eye's vision completely and severely limited the use of his left eye.

El ojo derecho de Don Sîmon estaba descolorido y vidrioso mientras se sentaba estoicamente, masticando hojas de coca, en una pequeña choza afuera de su mina en la montaña Cerro Rico sobre la ciudad de Potosí, en el suroeste de Bolivia. El accidente de dinamita tres semanas antes le había robado la visión del ojo por completo y limitado severamente el uso del ojo izquierdo.

Two days later, in a tiny cave, deep underground, lit only by the beam of his headlamp, this veteran of 32 years in the mines packed dynamite and ammonium nitrate into a cavity he had chiselled into solid rock. After lighting the fuse, he escaped through a crawl space no wider than him. The dull thud of an explosion brought a ton or more of zinc ore down, ready to be collected and manhandled to the surface.

Dos días después, en una cueva diminuta, en las profundidades del subsuelo, iluminada únicamente por el haz de su faro, este veterano de 32 años en las minas empacó dinamita y nitrato de amonio en una cavidad que había cincelado en roca sólida. Después de encender la mecha, escapó por un espacio de acceso no más ancho que él. El ruido sordo de una explosión trajo una tonelada o más de mineral de zinc, listo para ser recogido y manejado a la superficie.

Mining in the Cerro Rico is something of a gamble. Some find veins of silver and get rich, taking themselves and their families out of the mountain, setting up businesses in ore refinement or tourism. Some strike reliable and abundant sources of quality zinc ore and make a good living. Some find almost nothing, get injured or die of silicosis, cave-ins and wagon accidents.

La minería en el Cerro Rico es una especie de apuesta. Algunos encuentran vetas de plata y se enriquecen, sacando a sí mismos y a sus familias de la montaña, estableciendo negocios en la refinación de minerales o el turismo. Algunos encuentran fuentes confiables y abundantes de mineral de zinc de calidad y se ganan la vida bien. Algunos no encuentran casi nada, se lesionan o mueren de silicosis, derrumbes y accidentes de vagones.

Cerro Rico, which translates as 'Rich Hill', contains some of the world's oldest and most productive mines. Discovered by chance in 1545, while Diego de Huallpa was searching for an Inca shrine at the behest of the Conquistadors, the abundant silver was soon bankrolling the Spanish Empire. Potosî, the settlement below the mountain, became one of the most important cities of the New World and the site of the colonial mint.

Cerro Rico, que se traduce como 'Rich Hill', contiene algunas de las minas más antiguas y productivas del mundo. Descubierta por casualidad en 1545, mientras Diego de Huallpa buscaba un santuario inca a instancias de los conquistadores, la abundante plata pronto financió el Imperio español. Potosí, el asentamiento debajo de la montaña, se convirtió en una de las ciudades más importantes del Nuevo Mundo y el sitio de la ceca colonial.

The Cerro Rico has another, much older name, Surmaq Urqu, or 'Beautiful Mountain' in Quechua. It's difficult today to look past the almost five centuries of industrial evisceration that has scarred the peak with pits, holes and rubble-strewn terraces. In 2011 the top of the Cerro Rico began to cave in due to the rat’s nest of tunnels dug through it weakening its structure. Filling in with ultra-light cement is just a stopgap and there is a rumour among the miners that the whole mountain could collapse in on itself, layer by layer. There is no map or plan of the tunnel systems, the 180 operational mines are worked by experience and received knowledge, so there is little hope of a definitive solution.

El Cerro Rico tiene otro nombre mucho más antiguo, Surmaq Urqu, o 'Montaña Hermosa' en quechua. Hoy en día es difícil mirar más allá de los casi cinco siglos de evisceración industrial que ha marcado la cima con hoyos, hoyos y terrazas llenas de escombros. En 2011, la cima del Cerro Rico comenzó a derrumbarse debido a que el nido de ratas de túneles cavados a través de él debilitó su estructura. Rellenar con cemento ultraligero es solo una solución provisional y hay un rumor entre los mineros de que toda la montaña podría colapsar sobre sí misma, capa por capa. No hay mapa ni plano de los sistemas de túneles, las 180 minas operativas se trabajan por experiencia y conocimiento recibido, por lo que hay pocas esperanzas de una solución definitiva.

The human, as well as the environmental cost is also staggeringly high. Some writers have estimated a total of between 4 and 8 million people could have died in the mountain since the 16th century, mostly slaves. After black Africans brought in from the Atlantic colonies began to die to droves, the Spanish invaders decided to indenture the local Quechua population, compelling them to do six months forced labour in the mines every seven years. The Quechua, who were better accustomed to the altitude, climate and cramped working spaces were far more useful to the Spanish, although treated little better than their African counterparts.

El costo humano, así como el ambiental, también es asombrosamente alto. Algunos escritores han estimado que un total de entre 4 y 8 millones de personas podrían haber muerto en la montaña desde el siglo XVI, en su mayoría esclavos. Después de que los africanos negros traídos de las colonias del Atlántico comenzaran a morir en masa, los invasores españoles decidieron contratar a la población quechua local, obligándolos a realizar seis meses de trabajos forzados en las minas cada siete años. Los quechuas, que estaban mejor acostumbrados a la altitud, el clima y los espacios de trabajo reducidos, eran mucho más útiles para los españoles, aunque tratados poco mejor que sus homólogos africanos.

After independence was won from Spain in 1825, the slavery ended. In 1901 a period of corporate ownership led to intensive extraction that severely impacted the local ecosystem through deforestation for timber supports and the damming and contamination of water sources. In 1994 after the failure of the nationalised mines under the state-run company COMIBOL, mining cooperatives began to appear, with little oversight or regulation. Today the co-ops on the Cerro Rico number 38 and they run themselves with complete autonomy. The Bolivian government, it seems, is happy to leave the miners to their own devices, as long as they can collect the tax.

Después de la independencia de España en 1825, terminó la esclavitud. En 1901, un período de propiedad corporativa condujo a una extracción intensiva que impactó severamente el ecosistema local a través de la deforestación para los soportes madereros y la represa y contaminación de las fuentes de agua. En 1994, luego del fracaso de las minas nacionalizadas bajo la empresa estatal COMIBOL, comenzaron a aparecer las cooperativas mineras, con poca supervisión o regulación. Hoy las cooperativas del Cerro Rico número 38 y se dirigen con total autonomía. El gobierno boliviano, al parecer, está feliz de dejar a los mineros con sus propios dispositivos, siempre que puedan cobrar el impuesto.

There is another option for the miners of the Cerro Rico, as hard as it may be to believe, there is a thriving tourist industry that centres on the mines, taking paying visitors into the first, relatively safe level. Potosî is littered with tour agencies offering such trips and there is some debate as to the ethics. Even the Lonely Planet guide cautions "We urge you not to underestimate the dangers involved with going into the mines and to consider the voyeuristic factor involved in seeing other people's suffering". However, 37 year old Pedro, an ex-miner and owner of the B ig Deal Tours agency is having none of it.

Hay otra opción para los mineros del Cerro Rico, por difícil que sea de creer, hay una industria turística próspera que se centra en las minas, llevando a los visitantes de pago al primer nivel relativamente seguro. Potosí está plagado de agencias de viajes que ofrecen tales viajes y existe cierto debate sobre la ética. Incluso la guía de Lonely Planet advierte: "Le instamos a que no subestime los peligros que entraña entrar en las minas y que considere el factor voyerista que implica ver el sufrimiento de otras personas". Sin embargo, Pedro, de 37 años, exminero y propietario de la agencia B ig Deal Tours, no acepta nada de eso.

Short and sturdily built with dark skin and a thick head of hair, Pedro's booming, lyrical voice carries above the early morning bustle of the Mercado de Mineros. "Don't worry!" he grins, as he throws a stick of dynamite at the feet of an Australian tour group, eliciting some to jump back in fright. "It's perfectly safe. You need this to set it off", he says, mock-biting the detonator on the end of a green fuse. The miner's market is the first stop on the often twice-daily tours that Pedro and his company run into the mines. The tourists buy small gifts for the miners: coca leaves, cigarettes, sodas and dynamite. On Friday's the shopping list also includes 96% grain alcohol.

De estatura baja y robusta, de piel oscura y una espesa cabellera, la voz lírica y retumbante de Pedro se eleva por encima del bullicio matutino del Mercado de Mineros. sonríe mientras arroja una barra de dinamita a los pies de un grupo de turistas australiano, lo que provoca que algunos salten asustados. "Es perfectamente seguro. Necesitas esto para activarlo", dice, mordiendo el detonador en el extremo de una mecha verde. El mercado de los mineros es la primera parada en los recorridos a menudo dos veces al día que Pedro y su compañía realizan en las minas. Los turistas compran pequeños obsequios para los mineros: hojas de coca, cigarrillos, refrescos y dinamita. Los viernes, la lista de compras también incluye alcohol de grano al 96%.

From a mining family, his father died at 55 with 40 years experience in the Cerro Rico, Pedro considers the work dignified and important, "The mines can make you rich but you always have at least something for your belly". However, to hear him tell it, most miners don't want their children to follow them down into the darkness. "I've heard miners say that they are ready to die now because their children have an education. They don't have to work in the mines". "I've taken all three of my brothers out of the mines", Pedro says proudly, miming something akin to picking apples from a basket.

De familia minera, su padre falleció a los 55 años con 40 años de experiencia en el Cerro Rico, Pedro considera el trabajo digno e importante, "Las minas te pueden hacer rico pero siempre tienes al menos algo para la barriga". Sin embargo, al escucharlo decirlo, la mayoría de los mineros no quieren que sus hijos los sigan hacia la oscuridad. "Escuché a los mineros decir que están listos para morir ahora porque sus hijos tienen una educación. No tienen que trabajar en las minas". "Saqué a mis tres hermanos de las minas", dice Pedro con orgullo, imitando algo parecido a recoger manzanas de una canasta.

Pedro claims that the tours run by ex-miners are, in fact, perfectly ethical. For one thing, the gifts bought by the tourists help the often very poor miners to have a higher standard of living. It's estimated that the average miner spends 13% of his wages on coca-leaves, an essential aid to physical work at an altitude of well over 4000m. When you consider that a day's supply of coca can be bought for just 5Bs (0.75 USD), it becomes apparent that these small gifts can make a big difference. His operation also leaves a proportion of the money they make in the mines themselves, helping to fund celebrations and giving aid to the families of injured miners. However, the most important aspect for Pedro is that it offers a path out.

Pedro afirma que los recorridos realizados por ex mineros son, de hecho, perfectamente éticos. Por un lado, los regalos comprados por los turistas ayudan a los mineros a menudo muy pobres a tener un nivel de vida más alto. Se estima que el minero promedio gasta el 13% de su salario en hojas de coca, una ayuda esencial para el trabajo físico a una altitud de más de 4000 m. Cuando se considera que el suministro de coca para un día se puede comprar por solo 5Bs (0,75 USD), se hace evidente que estos pequeños obsequios pueden marcar una gran diferencia. Su operación también deja una parte del dinero que ganan en las propias minas, ayudando a financiar celebraciones y brindando ayuda a las familias de los mineros heridos. Sin embargo, el aspecto más importante para Pedro es que ofrece un camino de salida.

The path into the mines of the Cerro Rico is much more frequently trodden than the path out and often at an alarmingly young age. Getting a job is as easy as turning up and asking and there are no educational, literacy or class barriers. You certainly don't need papers. One miner told a story of a Mexican traveller who was robbed of his money. He spent three months working in the mines undocumented, until he had enough to get home. All this is great news if you need a job but the lack of scrutiny does expose children to a hazardous and potentially deadly working environment.

El camino hacia las minas del Cerro Rico se transita con mucha más frecuencia que el camino de salida y, a menudo, a una edad alarmantemente joven. Conseguir un trabajo es tan fácil como presentarse y preguntar y no hay barreras educativas, de alfabetización o de clase. Ciertamente no necesitas papeles. Un minero contó la historia de un viajero mexicano al que le robaron su dinero. Pasó tres meses trabajando en las minas indocumentado, hasta que tuvo suficiente para llegar a casa. Todo esto es una gran noticia si necesita un trabajo, pero la falta de escrutinio expone a los niños a un entorno laboral peligroso y potencialmente mortal.

The official age for starting to mine in the Cerro Rico is 18 but next to a set of disused tracks, deep in the Candalaria mine, Alex, 14, sits making Taco, explosive charges from dynamite, ammonium nitrate and gravel, packed into newspaper wads. During the summer holidays, many teenage boys who need a wage to help support their families venture into the mine, often alongside fathers or older siblings. Alex wears a shy expression and doesn't talk much but says he is making the Taco for a team of older miners drilling ore from a seam, further in. In the Grito De Piedra (‘Scream Of The Stone’) mine, Samwell, 15, breaks rocks with a sledgehammer. Alongside his father, Samwell is looking for Zinc ore in the rubble. He is currently on holiday from school.

La edad oficial para comenzar a minar en el Cerro Rico es de 18 años, pero junto a un conjunto de pistas en desuso, en lo profundo de la mina Candalaria, Alex, de 14 años, se sienta haciendo Taco, cargas explosivas de dinamita, nitrato de amonio y grava empaquetados en fajos de periódicos. Durante las vacaciones de verano, muchos adolescentes que necesitan un salario para ayudar a mantener a sus familias se aventuran en la mina, a menudo junto con sus padres o hermanos mayores. Alex tiene una expresión tímida y no habla mucho, pero dice que está haciendo el Taco para un equipo de mineros mayores que perforan mineral desde una veta, más adentro. En la mina Grito De Piedra ('El grito de la piedra'), Samwell , De 15 años, rompe rocas con un mazo. Junto a su padre, Samwell busca mineral de zinc entre los escombros. Actualmente está de vacaciones en la escuela.

The mines are a labyrinth that Daedalus could only have dreamed of constructing. Interlinking shafts and tunnels, many with no structural support of either rock or wood, some nearly 500 years old, criss-cross the Cerro Rico. An X-Ray of the mountain would probably resemble Swiss cheese. Miners, guided by headlamps, experience and an almost preternatural sense of direction, navigate the maze with ease.

After winding up and down through spaces at times so tight that they necessitate a commando crawl, climbing and descending sets of rotten ladders, wobbling in abysses of blackness and dodging mine carts loaded with tons of ore that careen, loosely guided by their handlers through narrow tunnels, it is possible to drop from one mine to another. In this case from Candalaria, to the Santa Ellena mine.

Las minas son un laberinto que Dédalo solo podría haber soñado construir. Pozos y túneles interconectados, muchos de ellos sin soporte estructural de roca o madera, algunos de casi 500 años, atraviesan el Cerro Rico.Una radiografía de la montaña probablemente se parecería al queso suizo. Los mineros, guiados por los faros, la experiencia y un sentido de dirección casi sobrenatural, navegan por el laberinto con facilidad.

Después de subir y bajar por espacios a veces tan estrechos que necesitan un comando gateando, trepando y descendiendo juegos de escaleras podridas, tambaleándose en abismos de negrura y esquivando carros mineros cargados con toneladas de mineral que se precipitan, guiados libremente por sus manejadores a través de estrechos túneles, es posible caer de una mina a otra. En este caso desde Candalaria, hasta la mina Santa Ellena.

At this depth it gets hot, very hot. The thin, oxygen depleted air of the altitude feels thick and is even harder to breathe as the light from headlamps reflects off turquoise stalactites of copper sulphate, formed from centuries of water seepage. Here, teams of men fill huge buckets with ore ready to be winched up through deep shafts, to the surface. The buckets can weigh 300Kg and many of these winches are hand operated. The strength it must take to exert the body so much in such an environment is almost unimaginable.

A esta profundidad hace calor, mucho calor. El aire delgado y sin oxígeno de la altitud se siente espeso y es aún más difícil de respirar ya que la luz de los faros se refleja en las estalactitas turquesas de sulfato de cobre, formadas por siglos de filtraciones de agua. Aquí, equipos de hombres llenan enormes cubos con mineral listo para ser transportado a través de pozos profundos hasta la superficie. Los baldes pueden pesar 300 kg y muchos de estos cabrestantes se operan manualmente. La fuerza que debe tomar el cuerpo para ejercer tanto en un entorno así es casi inimaginable.

Despite conditions that many in developed countries would consider a form of hell, it's easy to see why there is almost affection for the mines of the Cerro Rico amongst its workers. If you have no job and you have the guts, or are desperate enough, the mines will always provide employment. In Bolivia, one of the poorest countries in Latin America, without a functioning social safety net, this is not something to be sniffed at. Even in death, the mines can provide a lifeline for a miner's family.

A pesar de condiciones que muchos en países desarrollados considerarían una forma de infierno, es fácil ver por qué hay casi afecto por las minas del Cerro Rico entre sus trabajadores. Si no tiene trabajo y tiene las agallas, o está lo suficientemente desesperado, las minas siempre le proporcionarán empleo. En Bolivia, uno de los países más pobres de América Latina, sin una red de seguridad social en funcionamiento, esto no es algo que se pueda despreciar. Incluso en la muerte, las minas pueden proporcionar un salvavidas para la familia de un minero.

Doña Carmen, who inexplicably wears a broad and constant smile under her wide-brimmed Andean hat, lives in a small, ramshackle building with the 3 youngest of her 14 children, outside of the Grito de Piedra mine. A Quechua speaker from a rural village with no education, when her husband died of silicosis, a lung disease caused by breathing the dust and particles that choke the underground environment, Doña Carmen and her family would have been destitute. Instead, they find a living collecting the scraps of minerals left by the dumper trucks that take the ore to refineries and are paid by the mining cooperatives to act as night-time security. It isn't much but it is, seen through the prism of relativism, a living. Apparently this is a common setup for the widows of miners.

Doña Carmen, que inexplicablemente luce una amplia y constante sonrisa bajo su sombrero andino de ala ancha, vive en un edificio pequeño y destartalado con los 3 más pequeños de sus 14 hijos, en las afueras de la mina Grito de Piedra. Una hablante de quechua de un pueblo rural sin educación, cuando su esposo murió de silicosis, una enfermedad pulmonar causada por respirar el polvo y las partículas que ahogan el ambiente subterráneo, Doña Carmen y su familia se habrían quedado en la indigencia. En cambio, se ganan la vida recolectando los restos de minerales que dejan los camiones volquete que llevan el mineral a las refinerías y las cooperativas mineras les pagan para que actúen como seguridad nocturna. No es mucho, pero es, visto a través del prisma del relativismo, una vida. Aparentemente, esta es una configuración común para las viudas de los mineros.

Self regulated and managed, the cooperatives operate with few but very well adhered to rules. Once a miner is minted in his own right, a process that takes between two and six years of doing the worst jobs for other miners, he can either choose to continue working for others or strike out on his own. Digging his own tunnels and shafts into the hard rock, if on his first day he finds a fortune in silver, a miner who has found nothing much for 20 years would never even think of stealing from his colleague's vein. To do so would mean dishonour and expulsion from the co-op.

Autorreguladas y administradas, las cooperativas operan con pocas pero muy bien adheridas a las reglas. Una vez que un minero se acuña por derecho propio, un proceso que lleva entre dos y seis años haciendo los peores trabajos para otros mineros, puede optar por seguir trabajando para otros o emprender el camino por su cuenta. Cavando sus propios túneles y pozos en la roca dura, si en su primer día encuentra una fortuna en plata, un minero que no ha encontrado mucho durante 20 años ni siquiera pensaría en robarle la vena a su colega. Hacerlo significaría deshonra y expulsión de la cooperativa.

Aside from the means to live, it's obvious that the other thing the mines of the Cerro Rico provide is a community. Miners who are injured and unable to work are often helped financially by others and in the event of accidents and cave-ins, all the other miners will down tools to help their compañeros. This kind of mutual reliance breeds a strong sense of kinship, as does an understandably high level of superstition and adherence to ritual.

Aparte de los medios para vivir, es obvio que la otra cosa que brindan las minas del Cerro Rico es una comunidad. Los mineros que se lesionan y no pueden trabajar a menudo son ayudados económicamente por otros y en caso de accidentes y derrumbes, todos los demás mineros bajarán herramientas para ayudar a sus compañeros. Este tipo de dependencia mutua genera un fuerte sentido de parentesco, al igual que un nivel comprensiblemente alto de superstición y adherencia al ritual.

Each of the 180 mines contains a statue of El Tio (The Uncle), built by the miners themselves. Resembling the devil, although I'm told many times "The Andean devil, not the Christian devil", El Tio's clay body contains a heart of high quality silver ore, his glass eyes, set in a horned head, shine the way to the minerals, and the boots on his feet mark him out as a fellow miner and friend. His huge, engorged phallus is a sign of machismo (no women work in the Cerro Rico) and symbolises his mating with Pachamama, the Incan earth-mother-goddess, to produce minerals. El Tio controls everything underground as Pachamama does above, and therefore, he must be placated with offerings of coca leaves, alcohol and cigarettes, placed in and around his outstretched hands and open mouth. This is done frequently in the hope of good luck but most notably during a shared Friday afternoon ritual.

Cada una de las 180 minas contiene una estatua de El Tio (El Tío), construida por los propios mineros. Parecido al diablo, aunque me han dicho muchas veces "El diablo andino, no el diablo cristiano", el cuerpo de arcilla de El Tío contiene un corazón de mineral de plata de alta calidad, sus ojos de cristal, incrustados en una cabeza con cuernos, brillan el camino a los minerales y las botas en sus pies lo distinguen como un compañero minero y amigo. Su falo enorme e hinchado es un signo de machismo (no hay mujeres que trabajen en el Cerro Rico) y simboliza su apareamiento con Pachamama, la diosa madre-tierra inca, para producir minerales. El Tío controla todo bajo tierra como lo hace Pachamama arriba, y por lo tanto, debe ser aplacado con ofrendas de hojas de coca, alcohol y cigarrillos, colocados dentro y alrededor de sus manos extendidas y boca abierta. Esto se hace con frecuencia con la esperanza de tener buena suerte, pero sobre todo durante un ritual compartido el viernes por la tarde.

An exaggerated equivalent of knocking-off early and going to the pub, at 2pm on a Friday in the Grito de Piedra mine, the shapes of the men of the tunnels begin to coalesce out of the gloom. While it is certainly an excuse to celebrate surviving another week in the Cerro Rico, the weekly ritual around El Tio takes on another layer of meaning both in terms of bonding and spirituality. Bottles of Potosina, the local lager, and Ceibo, a 96% alcohol made from sugarcane (that smells like chrome cleaner and would, anywhere else, almost certainly be deemed illegal to sell for human consumption), are placed at the feet of the mine's Presidenté.

Equivalente exagerado de desprenderse temprano e ir al pub, a las 2 de la tarde de un viernes en la mina Grito de Piedra, las formas de los hombres de los túneles comienzan a fundirse en la penumbra. Si bien es sin duda una excusa para celebrar haber sobrevivido una semana más en el Cerro Rico, el ritual semanal alrededor de El Tío adquiere otra capa de significado tanto en términos de vinculación como de espiritualidad. Botellas de Potosina, la lager local, y Ceibo, un alcohol al 96% elaborado con caña de azúcar (que huele a limpiador de cromo y que, en cualquier otro lugar, se consideraría ilegal vender para consumo humano), se colocan en el pies del P residenté de la mina.

José Garabito, the current Presidenté of Grito de Piedra, a thin, bright eyed and obviously intelligent man in his mid-thirties, pours out the first round, a task the men share left to right, as everyone lights cigarettes and dips into bags of coca leaves. The first drops of drink, for El Tio and Pachamama, always hit the ground. Although the cares of the week are not easily forgotten, two miners, Moises and Francisco, grumble about the falling price of a certain type of ore (less than 1000Bs, 145 USD, for 8 tons) and rising government taxes; after several rounds it all descends into raucous joking and piss-taking. Miners have a notoriously vicious and dark sense of humour but it's all done with a wide grin.

José Garabito, el actual presidente de Grito de Piedra, un hombre delgado, de ojos brillantes y obviamente inteligente en sus treinta y tantos, derrama la primera ronda, una tarea que los hombres comparten de izquierda a derecha, mientras todos encienden cigarrillos y se bañan. en bolsas de hojas de coca. Las primeras gotas de bebida, para El Tio y Pachamama, siempre caen al suelo. Aunque las preocupaciones de la semana no se olvidan fácilmente, dos mineros, Moisés y Francisco, se quejan de la caída del precio de cierto tipo de mineral (menos de 1000Bs, 145 USD, por 8 toneladas) y el aumento de los impuestos gubernamentales; después de varias rondas, todo se convierte en bromas estridentes y meadas. Los mineros tienen un sentido del humor notoriamente vicioso y oscuro, pero todo se hace con una amplia sonrisa.

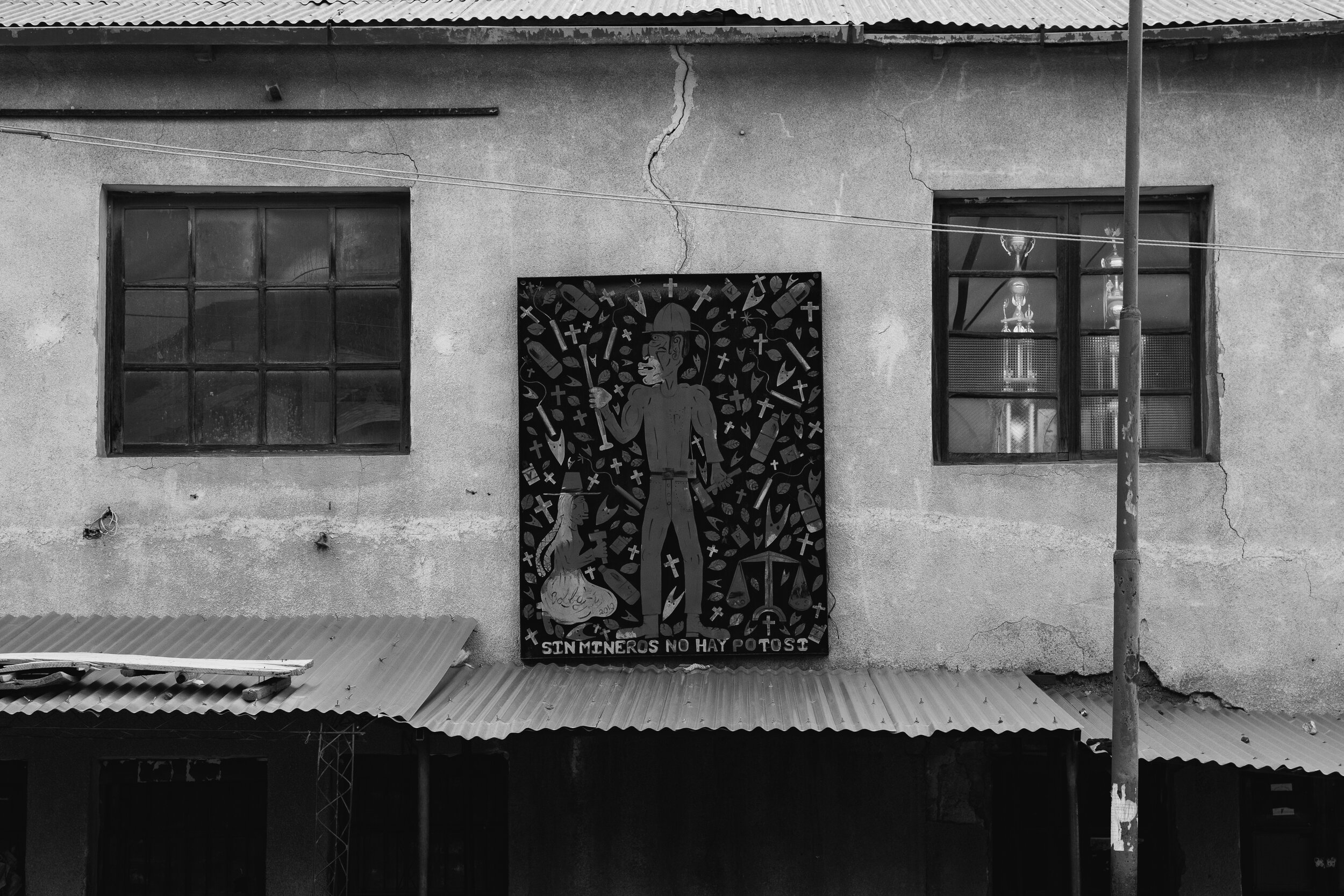

"Sin mineros, no hay Potosî" or "without miners, you don't have Potosî" is a common slogan in the city and for obvious reasons. Even in the modern age, Cerro Rico employs around 15000 men, at least 10% of the working age population. It's difficult to envisage how the area would survive economically without the industry and the secondary tourism that it attracts. In the high, cold and windswept environs of this remote part of South-western Bolivia, there aren't a lot of other options. There is some talk of mineral depletion leading to an eventual collapse and rumours of foreign corporations attempting to buy the rights to top-down mining are ever present, but for now, the cooperative mines are going nowhere.

"Sin mineros, no hay Potosî" o "sin mineros, no tienes Potosî" es un lema común en la ciudad y por razones obvias. Incluso en la era moderna, Cerro Rico emplea alrededor de 15.000 hombres, al menos el 10% de la población en edad de trabajar. Es difícil imaginar cómo la zona sobreviviría económicamente sin la industria y el turismo secundario que atrae. En los alrededores altos, fríos y azotados por el viento de esta parte remota del suroeste de Bolivia, no hay muchas otras opciones. Se habla de un agotamiento de los minerales que conduce a un eventual colapso y los rumores de corporaciones extranjeras que intentan comprar los derechos de la minería de arriba hacia abajo están siempre presentes, pero por ahora, las minas cooperativas no van a ninguna parte.

It may seem difficult or even callous to regard the mines of Potosî with anything approaching positivity, there are a myriad of reasons not to. Child labour, danger, horrendous conditions, injury, death, poverty. These are serious problems and until the Bolivian government provides adequate, material support to the mining community to improve their lot, there is little that will change. On the other hand, Cerro Rico provides employment, putting food on the tables of thousands of families, a secondary tourist economy and the chance of making far more than the country's minimum wage. It also fosters a tight-knit and cohesive community. After nearly 500 years it seems that the Rich Hill still doles out both hope and hardship to those who live in her shadow.

Puede parecer difícil o incluso insensible considerar las minas de Potosí con algo que se acerque a la positividad, hay una miríada de razones para no hacerlo. Trabajo infantil, peligro, condiciones horrendas, lesiones, muerte, pobreza. Estos son problemas graves y hasta que el gobierno boliviano brinde un apoyo material adecuado a la comunidad minera para mejorar su situación, es poco lo que cambiará. Por otro lado, Cerro Rico proporciona empleo, pone comida en las mesas de miles de familias, una economía turística secundaria y la posibilidad de ganar mucho más que el salario mínimo del país. También fomenta una comunidad unida y cohesionada. Después de casi 500 años, parece que Rich Hill todavía reparte esperanza y sufrimiento a quienes viven a su sombra.