A First Descent

The Story of the First Rafting Expedition down the Futaleufú River

La historia de la primera expedición de rafting por el río Futaleufú

by/por Peter Fox, originally published by Patagon Journal

Up until last year, I had run the Futaleufú River exactly once. A whole lot of people know a lot more about it than I do. But there are only a small group of us who knew the Futaleufú before it became THE Futaleufú. As part of the crew on the first raft expedition on the river in 1985, I had the good fortune to make its acquaintance when it was just a beautiful blue river disappearing into deep mountain gorges, near a town of the same name, in the southern mountains of Chile.

Hasta el año pasado, había corrido el río Futaleufú exactamente una vez. Mucha gente sabe mucho más sobre esto que yo. Pero solo somos un pequeño grupo que conocimos al Futaleufú antes de que se convirtiera en EL Futaleufú. Como parte de la tripulación de la primera expedición en balsa por el río en 1985, tuve la suerte de conocerlo cuando era solo un hermoso río azul que desaparecía en las profundas gargantas de las montañas, cerca de una ciudad del mismo nombre, en el sur. montañas de Chile.

All 4 boats started close together above Throne Room We were calling this rapid by the local’s name, “Salto Feo.” The first raft accelerated so fast that it is almost through the rapid and the other boats have barely moved. | Photo by Eric Nies

Today a person from any corner of the globe can go online and book a trip to run the Futaleufú. In 1985, the only way to be part of the very first Futaleufú trip was to be friends with Steve Currey and Dan Bolster.

Hoy en día, una persona de cualquier rincón del mundo puede conectarse a Internet y reservar un viaje para ejecutar el Futaleufú. En 1985, la única forma de ser parte del primer viaje de Futaleufú era ser amigo de Steve Currey y Dan Bolster.

1985 first raft expedition on Futaleufú. Daniel Bolster topping off his 22′ self bailing Maravia at put-in next to a local rowboat used to reach farms across the river without road access. | Photo by Peter Fox

Brad Lord and I were long time guiding partners with Dan and the three of us were part of Steve’s crew on Chile’s legendary Bio Bio River. We came with Steve to row four big yellow Maravia rafts down the Fu. With us were a hand picked group of adventurous clients that Steve knew from past trips with Steve Currey Expeditions.

Brad Lord y yo fuimos socios guías de Dan durante mucho tiempo y los tres éramos parte del equipo de Steve en el legendario río Bio Bio de Chile. Vinimos con Steve para remar en cuatro grandes balsas Maravia amarillas por el Fu. Con nosotros estaba un grupo cuidadosamente seleccionado de clientes aventureros que Steve conocía de viajes anteriores con Steve Currey Expeditions.

“Over the next four days, the Futaleufu river would nearly take one of our lives and leave us feeling connected to it forever. ”

“Durante los siguientes cuatro días, el río Futaleufú casi nos quita la vida y nos deja sintiéndonos conectados a él para siempre. "

It was February 1985. We all stood on a beach a few miles upstream from the town in the drizzling rain with only a sketchy idea of what lay downstream. The total of what we knew was from Dan and I scouting from town a year before, followed by a couple of passes flying over in a small plane. Over the next four days, the Futaleufú River would nearly take one of our lives and leave us feeling connected to it forever.

Era febrero de 1985. Todos estábamos de pie en una playa a unas pocas millas río arriba del pueblo bajo la llovizna con sólo una idea vaga de lo que había río abajo. El total de lo que sabíamos era de Dan y yo explorando desde la ciudad un año antes, seguido de un par de pases volando en un avión pequeño. Durante los siguientes cuatro días, el río Futaleufú casi se llevaría una de nuestras vidas y nos haría sentir conectados a él para siempre.

1984 scout of Futaleufú by small plane. | Photo by Peter Fox

1985 was my last year of full time raft guiding. Dan and I had been working North American summers in California and South American summers in Chile for four years. After that I went off and got a job and raised a family. I was 62 years old and a completely different person when I returned to the Fu for the second time last year bringing along my wife and two grown children, all of them river guides.

1985 fue mi último año como guía de balsa a tiempo completo. Dan y yo habíamos trabajado los veranos norteamericanos en California y los veranos sudamericanos en Chile durante cuatro años. Después de eso, me fui, conseguí un trabajo y formé una familia. Tenía 62 años y era una persona completamente diferente cuando regresé al Fu por segunda vez el año pasado con mi esposa y dos hijos mayores, todos ellos guías de río.

The 1985 Expedition/La Expedición 1985

For this first rafting expedition on the Futaleufú, we brought years of experience doing multi day rafting trips on big rivers like the Salmon, the Colorado and the Bio Bio. The whitewater stretch of the Fu was only 45 kilometers, not very long by those standards. We budgeted three days to run it from the top with fully loaded oar boats carrying camping equipment, a full kitchen, food and all of our personal cameras and gear.

Para esta primera expedición de rafting en el Futaleufú, aportamos años de experiencia realizando viajes de rafting de varios días en grandes ríos como el Salmón, el Colorado y el Bio Bio. El tramo de aguas bravas del Fu tenía solo 45 kilómetros, no muy largo para esos estándares. Presupuestamos tres días para ejecutarlo desde la parte superior con botes de remo completamente cargados con equipo de campamento, una cocina completa, comida y todas nuestras cámaras y equipo personales.

The Callaqui. My boat for Steve Currey Expeditions. Twenty two feet long with 32″ tubes and no floor. Plywood decks hang from the frame. Named after the volcano overlooking the Bio Bio River canyon. | Photo by Peter Fox

If modern Fu trips carry gear at all, the most they bring is lunch. Nowadays, on many trips, the passengers stay in beautiful camps along the river in tent cabins with real beds. There are nice bathrooms with flush toilets. They soak in hot tubs with river views and eat delicious sit down meals in weatherproof comfort.

Today’s Fu guides are world-class experts, who know all the rapids. Some have guided the river for a decade or more. They carry passengers downstream in big but light and nimble rafts with a safety net of kayaks and catarafts out front. They know all the different sections of the river at different water levels.

Si los viajes modernos de Fu llevan equipo, lo máximo que traen es el almuerzo. Hoy en día, en muchos viajes, los pasajeros se alojan en hermosos campamentos a lo largo del río en cabañas de campaña con camas reales. Hay bonitos baños con inodoros con cisterna. Se sumergen en jacuzzis con vista al río y comen deliciosas comidas sentadas en una comodidad resistente a la intemperie.

Los guías de Fu de hoy son expertos de clase mundial, que conocen todos los rápidos. Algunos han guiado el río durante una década o más. Llevan a los pasajeros río abajo en balsas grandes pero ligeras y ágiles con una red de seguridad de kayaks y cataratas en el frente. Conocen todas las diferentes secciones del río en diferentes niveles de agua.

The walls of the Fu canyon go straight up thousands of feet. Any rain in the drainage gets funneled directly into the river, which can transform overnight. At some water levels most of the river is safe and accessible but after a rain, whole sections are considered too dangerous. There are three rapids where modern outfitters never run commercial passengers at all.

Standing on the beach with our passengers in their bright raincoats, we congratulated ourselves that it wasn’t raining as hard as the day before when we couldn’t see our hands in front of our faces. We had no knowledge of weather’s effect on water levels. We had world-class big water experience, two superb safety kayakers in Eric Nies and KB Medford, and perfect boats for running huge powerful water. The serene current flowing past us on that beach gave no clue of what lay ahead.

Las paredes del cañón de Fu se elevan directamente a miles de pies. Cualquier lluvia en el drenaje se canaliza directamente al río, que puede transformarse de la noche a la mañana. En algunos niveles de agua, la mayor parte del río es seguro y accesible, pero después de una lluvia, secciones enteras se consideran demasiado peligrosas. Hay tres rápidos donde los armadores modernos nunca transportan pasajeros comerciales.

Parados en la playa con nuestros pasajeros con sus impermeables brillantes, nos felicitamos porque no llovía tan fuerte como el día anterior cuando no podíamos vernos las manos frente a la cara. No teníamos conocimiento del efecto del clima en los niveles del agua. Tuvimos una gran experiencia en el agua de clase mundial, dos excelentes kayakistas de seguridad en Eric Nies y KB Medford, y botes perfectos para correr agua enorme y potente. La serena corriente que pasaba junto a nosotros en esa playa no nos daba ni idea de lo que nos esperaba.

Of the four rowers on the trip Steve was the most experienced. His father ran a rafting outfit and Steve grew up rafting. He had a quiet self-effacing way of not looking as big and strong as he really was, but he was one of the best rowers I ever saw. Unfortunately he is no longer with us. Steve passed away a few years ago.

Dan, Brad and I filled out his crew. We had received our primary big water educations from the Tuolumne River in California. We did our finishing school, on the Bio Bio, a river with the volume and power of the Grand Canyon and the technical challenges of the Tuolumne. The Bio Bio was a whitewater monster.

De los cuatro remeros en el viaje, Steve fue el más experimentado. Su padre tenía un equipo de rafting y Steve creció haciendo rafting. Tenía una manera tranquila y modesta de no verse tan grande y fuerte como realmente era, pero era uno de los mejores remeros que he visto. Desafortunadamente, ya no está con nosotros. Steve falleció hace unos años.

Dan, Brad y yo completamos su equipo. Habíamos recibido nuestra educación primaria sobre el agua grande del río Tuolumne en California. Hicimos nuestra escuela de acabado, en el Bio Bio, un río con el volumen y la potencia del Gran Cañón y los desafíos técnicos del Tuolumne. El Bio Bio era un monstruo de aguas bravas.

It was after a Bio Bio season that Dan and Steve were in a Puerto Montt hotel room pouring over topographic maps when they spotted a promising blue line inland from the tiny port of Chaiten.

The Bio Bio was under a death sentence. Its legendary rapids and the way of life in its canyon were to be drowned by massive hydroelectric dams. Steve and Dan were in search of the next great Chilean whitewater river.

Fue después de una temporada de Bio Bio que Dan y Steve estaban en una habitación de hotel de Puerto Montt revisando mapas topográficos cuando vieron una línea azul prometedora tierra adentro desde el pequeño puerto de Chaitén.

El Bio Bio estaba condenado a muerte. Sus legendarios rápidos y la forma de vida en su cañón serían ahogados por enormes represas hidroeléctricas. Steve y Dan estaban en busca del próximo gran río de aguas bravas chileno.

“We might as well have been from Mars with our bright colored Patagonia Baggies, fleece sweaters and our loco obsession with the river.”

“Bien podríamos haber sido de Marte con nuestras bolsitas Patagonia de colores brillantes, suéteres de lana y nuestra loca obsesión con el río”.

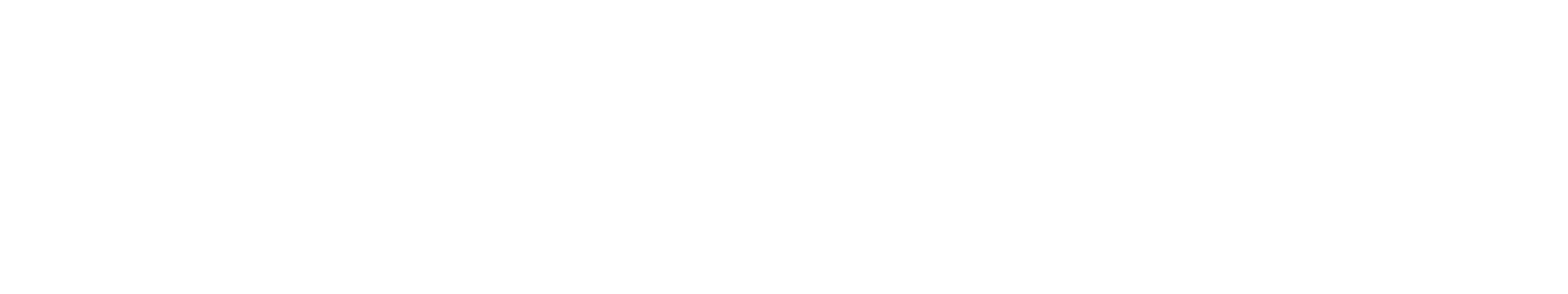

So a year before the ’85 descent, three of us followed Dan’s purposeful back and long strides south to go take a look. We were the first river runners in the Fu valley. We might as well have been from Mars with our bright colored Patagonia Baggies, fleece sweaters and our loco obsession with the river. The residents with their big smiles and their homespun wool hats and coats, were equally exotic to us.

Así que un año antes del descenso del 85, tres de nosotros seguimos la decidida espalda de Dan y dimos largas zancadas hacia el sur para echar un vistazo. Fuimos los primeros corredores de ríos en el valle de Fu. Bien podríamos haber sido de Marte con nuestras bolsitas Patagonia de colores brillantes, suéteres de lana y nuestra loca obsesión con el río. Los residentes con sus grandes sonrisas y sus abrigos y gorros de lana hechos en casa, fueron igualmente exóticos para nosotros.

In the town of Futaleufu with local friends names unknown. River guides left to right- Dave Burke, Karen Pilar, Daniel Bolster | Photo by Peter Fox

Life in Fu was like winding the clock back 50 years from the modern 1980’s to an older and simpler way of living. Buying a loaf of bread turned into an afternoon of talk over cups of tea. Chilean friends we met on the ferry pulled into town and asked the mayor, who happened to be the local butcher, if they could camp in the brand new school building. He just handed them the key. It was that kind of town. Hospitality was a way of life in this protected mountain Shangri La.

Our last night in town, we were literally taken by the elbows and ushered into a celebration at the community center and pulled into the middle of a dancing crowd of grinning dark haired locals. We towered over them with our light hair and big beards. By the end I was laughing so hard, propped against a row of wool coats hung on the wall that tears were running down my face.

La vida en Fu era como retroceder 50 años desde la moderna década de 1980 hasta una forma de vida más antigua y sencilla. Comprar una barra de pan se convirtió en una tarde de charla con tazas de té. Los amigos chilenos que conocimos en el ferry llegaron a la ciudad y le preguntaron al alcalde, que resultó ser el carnicero local, si podían acampar en el nuevo edificio de la escuela. Simplemente les entregó la llave. Era ese tipo de ciudad. La hospitalidad era una forma de vida en esta montaña protegida Shangri La.

Nuestra última noche en la ciudad, literalmente nos tomaron por los codos y nos llevaron a una celebración en el centro comunitario y nos detuvieron en medio de una multitud bailando de lugareños sonrientes de cabello oscuro. Los dominamos con nuestro cabello claro y grandes barbas. Al final me reía con tanta fuerza, apoyada contra una hilera de abrigos de lana colgados en la pared que las lágrimas corrían por mi rostro.

“The river was not as big as the Bio Bio, but the rapid had packed a more powerful punch than anything we had ever experienced.”

"El río no era tan grande como el Bio Bio, pero el rápido había tenido un golpe más poderoso que cualquier otra cosa que hayamos experimentado".

The weather cleared up our first afternoon on the river. The rest of the time it rained. When we hit the first major whitewater, the Infierno Canyon, our three-day timetable went out the window.

El tiempo mejoró nuestra primera tarde en el río. El resto del tiempo llovió. Cuando llegamos al primer gran blanco, el Infierno Canyon, nuestro horario de tres días se fue por la ventana.

Daniel Bolster scouting Infierno Canyon after bushwhacking through trail-less forest. | Photo by Peter Fox

At lower water, today this steep canyon is divided up into four distinct Class V or V+ rapids. The dripping steep forested canyon we saw in ’85 was one continuous stretch of whitewater that took us half a day to scout, bush whacking through the thick undergrowth for a mile to see its entire length. When we all arrived safely below the rapid we were in shock. The river was not as big as the Bio Bio, but the rapid had packed a more powerful punch than anything we had ever experienced. We called it “Surprise Canyon.” The boatmen looked around into each other’s eyes. We knew right then we were into something serious.

En aguas más bajas, hoy este cañón empinado se divide en cuatro rápidos Clase V o V + distintos. El cañón boscoso y empinado que goteaba que vimos en el '85 era un tramo continuo de aguas bravas que nos llevó medio día explorar, los arbustos golpeaban la espesa maleza durante una milla para ver toda su longitud. Cuando todos llegamos sanos y salvos por debajo del rápido, quedamos en estado de shock. El río no era tan grande como el Bio Bio, pero el rápido había tenido un golpe más poderoso que cualquier otra cosa que hubiéramos experimentado. Lo llamamos "Surprise Canyon". Los barqueros se miraron a los ojos. En ese momento supimos que estábamos metidos en algo serio.

Rapid we named “Surprise”, now named “Infierno” | Photo by Peter Fox

Brad Lord is and was a tough athlete and an excellent rower. It was his first season rowing in Chile. He had just handled the big Maravia raft on a high water Bio Bio trip, a significant benchmark of world rafting at that time. Where the Infierno canyon turned to the right, his boat had slid into an eddy that it took him a good 10 minutes to escape. The high water Fu was giving notice that it would be another level entirely.

Proceeding downstream we had to keep scouting major rapids while our time schedule kept crumbling and putting us under pressure to move as fast as we could.

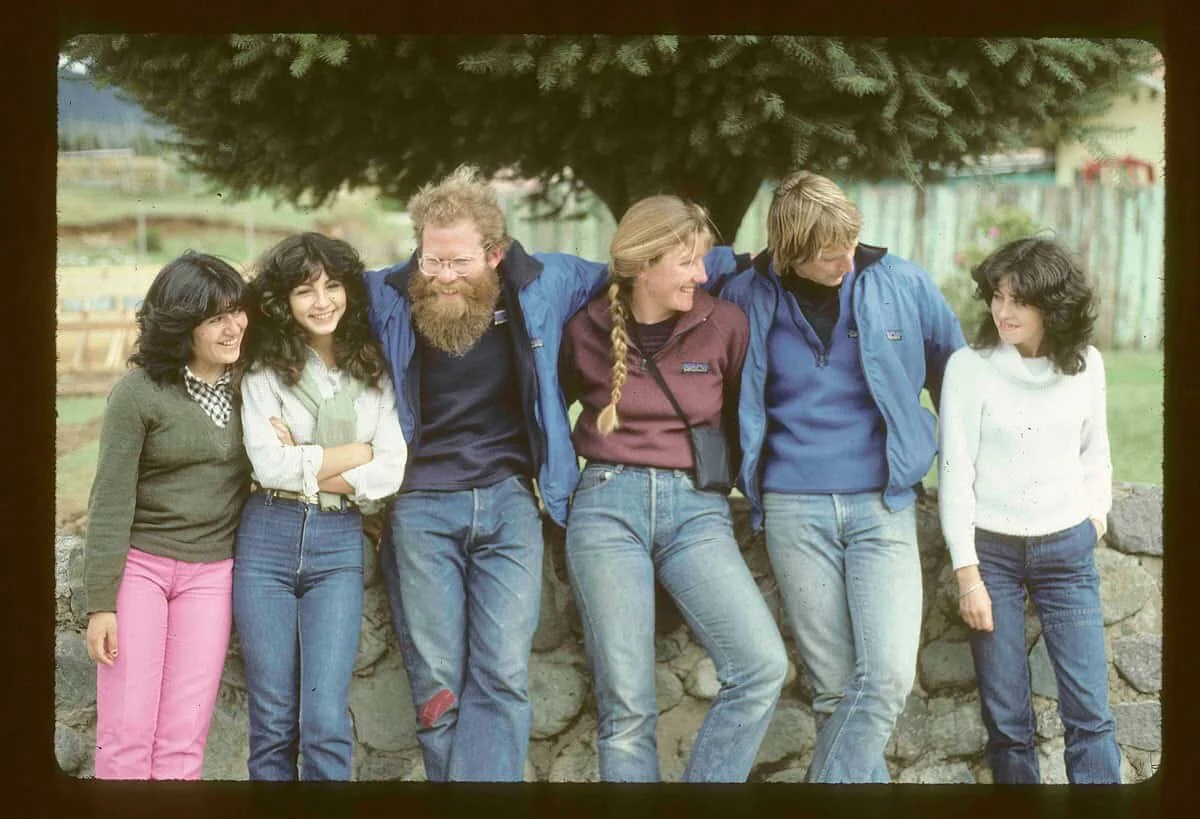

We had lost a half-day scouting Infierno Canyon, which was nothing compared to the 24 hours we spent solving Zeta, the first of the rapids that does not get run by modern outfitters.

Brad Lord es y fue un atleta duro y un excelente remero. Era su primera temporada remando en Chile. Acababa de manejar la gran balsa Maravia en un viaje Bio Bio en aguas altas, un punto de referencia significativo del rafting mundial en ese momento. Donde el cañón de Infierno giraba a la derecha, su bote se había deslizado en un remolino del que tardó unos buenos 10 minutos en escapar. El Fu del agua alta estaba dando aviso de que sería otro nivel por completo.

Continuando río abajo, tuvimos que seguir explorando los principales rápidos mientras nuestro horario se desmoronaba y nos presionó para movernos lo más rápido que pudiéramos.

Habíamos perdido medio día explorando el Cañón del Infierno, que no fue nada comparado con las 24 horas que pasamos resolviendo Zeta, el primero de los rápidos que no es manejado por los armadores modernos.

To safely run the rafts through Zeta, Danny Bolster rappelled down to this rock where he could rescue any boats that strayed into the keeper eddy (lower left of photo). Note driftwood stuck in the eddy. Two of our boats did go into the eddy and were rescued by Dan. | Photo by Brad Lord

We had a few moments of despair as we made a makeshift camp on the cobble above the zig zag where the river drops two stories through a throat of bedrock. All we wanted was to get the people and boats through safely. We ended up launching the rafts through the rapid unmanned. But to reach that point all the dangerous complications had to be addressed one by one. It wasn’t till the next day that we could put all the pieces in place to get us on our way downstream.

Tuvimos unos momentos de desesperación cuando hicimos un campamento improvisado en el adoquín sobre el zigzag donde el río desciende dos pisos a través de una garganta de lecho de roca. Todo lo que queríamos era que la gente y los barcos pasaran de forma segura. Terminamos lanzando las balsas a través del rápido sin tripulación. Pero para llegar a ese punto, todas las peligrosas complicaciones debían abordarse una por una. No fue hasta el día siguiente que pudimos poner todas las piezas en su lugar para ponernos en camino río abajo.

Empty raft finishing Zeta Rapid right side up and headed for the keeper eddy. | Photo by Peter Fox

All smiling faces below Throne Room. Brad’s oar was the only casualty. We were lucky. | Photo by Peter Fox

It seems amazing that we spent only about an hour looking at and successfully running Throne Room, the second rapid that never gets run with passengers these days. The only casualty was one of Brad’s yellow Carlisle oars busted in half.

That night we were worn down. We had been worried for days and hadn’t slept well at Zeta. Every ounce of our energy was going to keeping everyone safe through the rapids. The passengers were grumbling about the lousy camps. We were feeding them great meals and doing all the camp work like on any commercial river trip, while trying to make them believe everything was normal. Privately we were very focused. Our passengers were not exactly blissful, but they were ignorant to the extreme risk in what we were doing.

At dusk, when we were just serving dinner, four riders galloped on horseback into camp. Steve’s driver and some local ranchers had come to see why we were over a day late for our rendezvous. He gave us the bad news that the big rapid we were anticipating, now called Terminator, was not far downstream.

Parece sorprendente que solo pasamos una hora mirando y ejecutando con éxito Throne Room, el segundo rápido que nunca se ejecuta con pasajeros en estos días. La única víctima fue uno de los remos amarillos Carlisle de Brad roto por la mitad.

Esa noche estábamos agotados. Llevábamos días preocupados y no habíamos dormido bien en Zeta. Cada gramo de nuestra energía iba a mantener a todos a salvo a través de los rápidos. Los pasajeros se quejaban de los pésimos campamentos. Les dábamos excelentes comidas y hacíamos todo el trabajo del campamento como en cualquier viaje comercial por el río, mientras intentábamos hacerles creer que todo era normal. En privado estábamos muy concentrados. Nuestros pasajeros no estaban exactamente felices, pero ignoraban el riesgo extremo en lo que estábamos haciendo.

Al anochecer, cuando estábamos sirviendo la cena, cuatro jinetes galoparon a caballo hacia el campamento. El conductor de Steve y algunos ganaderos locales habían venido a ver por qué estábamos un día tarde para nuestra cita. Nos dio la mala noticia de que el gran rápido que estábamos anticipando, ahora llamado Terminator, no estaba muy lejos.

Locals come visit our river left camp on the Fu above Terminator. | Photo by Peter Fox

So on our fourth rainy morning after another wet night we spent interminable hours examining every inch of Terminator. This was the third of the rapids where even at lower water passengers are walked around by trail. We also had made the decision to walk our passengers, and so it was just the guides who returned to the rafts tied in the eddy above the giant rapid. Face to face, there was real honest doubt about whether we should even attempt it. A tiny mistake at the top would have dire consequences below.

Which was exactly how it happened. Brad’s boat swung a little wide while maneuvering at the set up, and ended up a couple of feet too far right. The huge rafts and their heavy plywood floors had run everything the river had thrown at us to this point. But you could never for a second let them pick up steam on a wrong course. They were hard to turn, let alone in huge water and they ran like a freight train in the direction they were pointed.

It was literally a matter of 24 inches or so in that pressure cooker situation that sent three of us into a route down the left side of the rapid and Brad down the right toward a cavernous hole in the surface of the river. His plunge into it, and his subsequent swim are captured on video. They are epic. Without a good life jacket and dry suit he would not have made it. For a few excruciating moments all of us—including Brad—didn’t think he would.

Así que en nuestra cuarta mañana lluviosa después de otra noche lluviosa pasamos horas interminables examinando cada centímetro de Terminator. Este fue el tercero de los rápidos donde, incluso en aguas más bajas, los pasajeros caminan por senderos. También habíamos tomado la decisión de llevar a nuestros pasajeros a pie, por lo que fueron solo los guías los que regresaron a las balsas atadas en el remolino sobre el gigantesco rápido. Cara a cara, había dudas sinceras sobre si deberíamos intentarlo. Un pequeño error en la parte superior tendría terribles consecuencias en la parte inferior.

Que fue exactamente como sucedió. El bote de Brad se abrió un poco mientras maniobraba en el montaje y terminó un par de pies demasiado a la derecha. Las enormes balsas y sus pesados pisos de madera contrachapada habían corrido todo lo que el río nos había arrojado hasta ese momento. Pero nunca ni por un segundo podría dejarlos tomar impulso en un camino equivocado. Eran difíciles de girar, y mucho menos en aguas enormes y corrían como un tren de carga en la dirección que les indicaban.

Fue literalmente una cuestión de 24 pulgadas más o menos en esa situación de olla a presión que nos envió a tres de nosotros a una ruta por el lado izquierdo del rápido y a Brad por el derecho hacia un agujero cavernoso en la superficie del río. Su zambullida en él y su posterior nado se capturan en video. Son épicos. Sin un buen chaleco salvavidas y un traje seco no lo habría logrado. Durante unos momentos insoportables, todos nosotros, incluido Brad, pensamos que no lo haría.

The raft stayed in the hole for 30 minutes while the river stripped it clean. After Brad was rescued the next thing we saw floating downstream, were ¾ inch plywood decks ripped to pieces like cardboard.

When the boat finally kicked free, Brad and our driver chased it down with the truck and managed to recover it. Already days behind schedule and all safe and in one piece, we decided we had done enough. Negotiating a night in the shelter of a pig barn, we called it a trip and packed the truck the next day with anything but a sense of disappointment. We had more than survived a remarkable river. Four boats had rowed it nearly flawlessly down to a margin of about 2 feet on one of the most impressive rafting rapids on earth.

La balsa permaneció en el agujero durante 30 minutos mientras el río la limpiaba. Después de que Brad fue rescatado, lo siguiente que vimos flotando río abajo fueron cubiertas de madera contrachapada de ¾ de pulgada desgarradas en pedazos como cartón.

Cuando el bote finalmente se soltó, Brad y nuestro conductor lo persiguieron con el camión y lograron recuperarlo. Ya con días de retraso y todo seguro y de una sola pieza, decidimos que habíamos hecho lo suficiente. Negociando una noche en el refugio de un establo de cerdos, lo llamamos un viaje y empacamos el camión al día siguiente con cualquier cosa menos una sensación de decepción. Habíamos sobrevivido con creces a un río extraordinario. Cuatro botes lo habían remado casi sin problemas hasta un margen de aproximadamente 2 pies en uno de los rápidos de rafting más impresionantes del mundo.

The Postscript/Posdata

Our trip would be the only raft descent of the Fu in the 1980’s. In March 1991, future outfitter, Eric Hertz, mounted a descent that included Steve and former Olympic kayaker Chris Spelius as a safety boater. His party rafted the entire length of the river with only the extremely risky Zeta portaged— and Steve got the chance to finally row the final 7 miles of the Futaleufú.

Nuestro viaje sería el único descenso en balsa del Fu en la década de 1980. En marzo de 1991, el futuro armador, Eric Hertz, realizó un descenso que incluyó a Steve y al ex kayakista olímpico Chris Spelius como navegantes de seguridad. Su grupo hizo rafting a lo largo del río con solo el extremadamente arriesgado Zeta transportado, y Steve tuvo la oportunidad de finalmente remar las últimas 7 millas del Futaleufú.

“The irony of this story is that we scouted the Fu to replace the threatened Bi Bio, and now the Fu is itself in serious jeopardy of being dammed.”

"La ironía de esta historia es que exploramos el Fu para reemplazar el Bi Bio amenazado, y ahora el Fu está en grave peligro de ser represado".

Dan and Steve’s vision came true. The Fu did become the next great Chilean rafting river, a world class and world famous whitewater destination.

It should be noted that there were kayak descents of the river dating back to 1985. Spelius led groups of paddlers down in the late 1980’s and his descents were instrumental in opening up the Fu to commercial boating. Since that time generations of guides and outfitters have made it safe and accessible to any who still seek a truly wild and beautiful place.

La visión de Dan y Steve se hizo realidad. El Fu se convirtió en el próximo gran río chileno de rafting, un destino de aguas bravas de fama mundial y de clase mundial.

Cabe señalar que hubo descensos en kayak del río que se remontan a 1985. Spelius condujo a grupos de remeros a finales de la década de 1980 y sus descensos fueron fundamentales para abrir el Fu a la navegación comercial. Desde entonces, generaciones de guías y proveedores de equipos lo han hecho seguro y accesible para cualquiera que todavía busque un lugar verdaderamente salvaje y hermoso.

The irony of this story is that we scouted the Fu to replace the threatened Bio Bio, and now the Fu is itself in serious jeopardy of being dammed. No matter how many battles are won, a free flowing river is never completely safe.

Late last year, we were all heartened to hear that Endesa, Chile’s largest energy company, had punted plans to build dams on the river. But the company still has the water rights, and recently requested a change in location, which legal experts suggest could be a move to re-activate the project. In response, the community is forming a new coalition to denounce plans to dam the Futaleufú and argue for local determination of Futaleufú’s future.

La ironía de esta historia es que exploramos el Fu para reemplazar el Bio Bio amenazado, y ahora el Fu está en serio peligro de ser represado. No importa cuántas batallas se ganen, un río que fluye libremente nunca es completamente seguro.

A fines del año pasado, nos alegró saber que Endesa, la empresa de energía más grande de Chile, había apostado por los planes de construir represas en el río. Pero la empresa aún tiene los derechos de agua y recientemente solicitó un cambio de ubicación, lo que los expertos legales sugieren que podría ser una medida para reactivar el proyecto. En respuesta, la comunidad está formando una nueva coalición para denunciar los planes de represar el Futaleufú y defender la determinación local del futuro de Futaleufú.

The goal is for the Futaleufú to receive permanent protection under Chilean and international law, a feat that Futaleufú Riverkeeper’s International Director, Patrick Lynch, says could take years to achieve and will require coordination at all levels.

Standing on the bank of the Fu thirty years later, I see a place in the world that is still only partially tamed. It remains dangerous and wild. Rafting it today with one of the excellent outfitters, we can touch and feel this wildness. The sparkling walls of aquamarine water rise up to bury the rafts. The guides expertly weave the boats past the danger, but the edge is never far away. They are focused and their hearts still pound.

El objetivo es que Futaleufú reciba protección permanente bajo la ley chilena e internacional, una hazaña que el Director Internacional de Futaleufú Riverkeeper, Patrick Lynch, dice que podría llevar años lograr y requerirá coordinación a todos los niveles.

De pie en la orilla del Fu treinta años después, veo un lugar en el mundo que todavía está solo parcialmente domesticado. Sigue siendo peligroso y salvaje. Rafting hoy con uno de los excelentes armadores, podemos tocar y sentir esta locura. Las paredes relucientes de agua color aguamarina se elevan para enterrar las balsas. Los guías tejen con destreza los barcos más allá del peligro, pero el borde nunca está lejos. Están concentrados y sus corazones aún palpitan.

At the bottom of Terminator, my two kids and I tasted the wildness when our raft drifted a few feet off its line. A powerful Fu wave blasted us into the water. We reviewed it in slow motion on a GoPro video and it happens in the blink of an eye.

Rescue boats were right there to pick us up, close to the same place where Brad was rescued 30 years ago. The Fu was having a little chuckle at our expense and reminding us of our place in the order of things. A much-needed reminder on a fast changing planet we need to save one wild place at a time, one special river at a time.

En la parte inferior de Terminator, mis dos hijos y yo probamos la locura cuando nuestra balsa se alejó unos metros de su línea. Una poderosa ola Fu nos arrojó al agua. Lo revisamos en cámara lenta en un video de GoPro y sucede en un abrir y cerrar de ojos.

Los botes de rescate estaban allí para recogernos, cerca del mismo lugar donde Brad fue rescatado hace 30 años. El Fu se estaba riendo un poco a costa nuestra y nos recordaba nuestro lugar en el orden de las cosas. Un recordatorio muy necesario en un planeta que cambia rápidamente, necesitamos salvar un lugar salvaje a la vez, un río especial a la vez.

Our truck on the ferry from Chaiten to Chilhoe after the trip. Dan Bolster and Brad Lord. Note the 1980 era river footwear. | Photo by Peter Fox